Microsoft has been quite active in the digital photography arena lately. One of its most promising contributions to the digital photography industry is HD Photo (formerly Windows Media Photo), which is currently being considered by the JPEG committee to become a standardized image format like that of JPEG. Currently it is tentatively called JPEG XR.

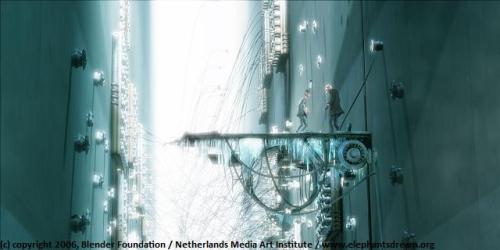

The main advantage of HD Photo over JPEG is that the former retains a far greater range of brightness and colors. Today’s digital cameras, especially digital single-lens reflex cameras (dSLRs), can capture far greater levels and range of brightness (bit depth and dynamic range) and colors (color gamut) than what is permitted to be saved by JPEG. Right now there are two main ways to overcome this: compress the ranges to fit within JPEG’s limitations, or use a file format known as RAW. The problem with the first method is that, while both the brightest and darkest details are retained, the subtle nuance between the two is lost. The implication of this is that when you try to fix an underexposed or overexposed image by adjusting the its levels and curves, steps in the brightness scale are more easily exaggerated and become visible, causing a phenomenal called posterization (see photo above). RAW on the other hand, while retaining all color and brightness information the camera has captured, requires post-processing in order to print and share over the Internet. In addition, RAW file formats are often proprietary and are not standardized between camera manufacturers, making compatibility troublesome. This is why you don’t see many photo kiosks accepting RAW files. HD Photo, if standardized and adopted, will bring the convenience of JPEG along with most (but not all) of the quality benefits of RAW.

The other major improvement over JPEG is that it supports progressive and regional decoding. To give a practical example: when opening a 12 megapixel image, even though your screen is only capable of showing around 1-4 megapixels, what HD Photo can do is to extract and decode only the portions of the image data necessary to render the smaller image, rather than loading all the 12 megapixels into memory which are not all visible. When you only want to zoom in to and edit a 1 megapixel area of the image, it can also only load in that region of data only. It is this technology that allows Microsoft Live Labs Photosynth and Microsoft Research HD View to render gigantic images so smoothly without overwhelming system and bandwidth resources.

HD Photo also brings along compression efficiency improvements over JPEG at the same time. According to Microsoft, “HD Photo offers compression with up to twice the efficiency of JPEG, with fewer damaging artifacts, resulting in higher-quality images that are one-half the file size.” This will give sports photographers a great alternative to RAW. A camera’s ability to capture fast sequences of action is limited by its buffer memory. The smaller the file size of each image, the more “action” that can be captured before the buffer fills up. JPEG’s smaller size is ideal for this type of photography, but at the cost of image quality; RAW on the other hand severely limits the number of shots that the buffer storage can accommodate. HD Photo offers the best of both worlds – high image quality approaching that of RAW with file sizes comparable to JPEG.

HD Photo also brings along compression efficiency improvements over JPEG at the same time. According to Microsoft, “HD Photo offers compression with up to twice the efficiency of JPEG, with fewer damaging artifacts, resulting in higher-quality images that are one-half the file size.” This will give sports photographers a great alternative to RAW. A camera’s ability to capture fast sequences of action is limited by its buffer memory. The smaller the file size of each image, the more “action” that can be captured before the buffer fills up. JPEG’s smaller size is ideal for this type of photography, but at the cost of image quality; RAW on the other hand severely limits the number of shots that the buffer storage can accommodate. HD Photo offers the best of both worlds – high image quality approaching that of RAW with file sizes comparable to JPEG.

Like any standard, it takes time to become well accepted by the industry. However, you can start experiencing the benefits of HD Photo today with a Photoshop plugin (for Windows and Mac) that saves images directly to the new format. Also, Chuck Westfall from Canon recently gave us a hint on the possibility of including HD Photo in future cameras. While JPEG is likely to remain mainstream well into the foreseeable future, HD Photo, once standardized, will bring much needed improvements to photographers, scientific and medical imaging, and post-processing users alike.

If you would like a technical explanation of the capabilities of HD Photo, I recommend the blog written by Bill Crow, the Program Manager for HD Photo.

HD Photo also brings along compression efficiency improvements over JPEG at the same time. According to

HD Photo also brings along compression efficiency improvements over JPEG at the same time. According to

Recent Comments